An article about the Spanish artist Santiago Sierra, that was originally published in After Nyne magazine.

Santiago Sierra is a Spanish artist who creates works that are seemingly morally bankrupt, and that initially inspire revulsion in the minds of most. The pointless menial labor of marginalised members of society is what Sierra uses as the raw materials with which to create his works, and it is this that people find the most distressing.

Previous works have included: paying illegal immigrants to sit under boxes in galleries for hours at a time; bricking a gallery worker inside a room for 10 days; and covering 10 Iraqis in hardening foam.

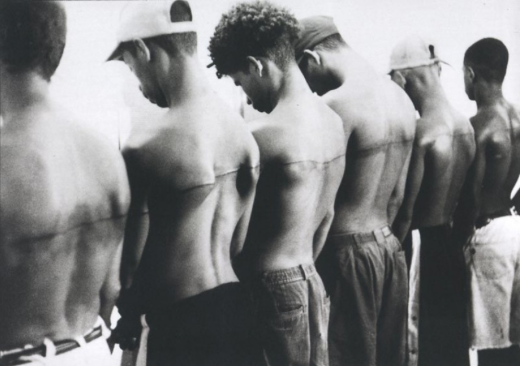

In one work 160cm Line Tattooed Four People – four prostitutes are paid in the price of a shot heroin, to have a line tattooed on their backs. The line is thin and straight, and spans the entire width of the back of one, continuing across all six. The tattoo machine needle echoes the needle through which the nominal amount of heroin will be administered, and the tattoo speaks of the permanency of the tattoo in contrast to the immediate and short-lived effects of the heroin.

In this work, the women involved have made a conscious choice to accept the tattoo for the recompense offered. The decision is theirs alone, yet to the viewer this is unarguably exploitative and insensitive. Heroin addiction is tragic in its banality, and this is something that Sierra exposes through his exploitation of these women, in an equally banal and tragic way.

For the individual women tattooed, this work is clearly exploitative and unethical, but — if by its execution the needs and struggles of the chemically dependent are exposed to a wider audience, then the work can serve some positive purpose. This work may serve society on the whole, as through its utter depravity it may encourage people to offer help to those affected by addiction in a similar way.

The problem here lies with a society that allows these people to become so desperate that they are willing to go to such lengths. Sierra himself explained the work saying:

“The tattoo is not the problem. The problem is the existence of social conditions that allow me to make this work.”

This exploitation of individuals in order to serve society on the whole is unpalatable, but it is this unpalatability that affects us so profoundly, thus creating a real empathy that would be unachievable through the use of mere statistics. The exploitation of a few to serve the greater good may be ethically ambiguous, but it is something that happens all across society and all throughout history, to varying degrees of severity.

The revulsion that these works create in the viewer can be incredibly powerful in the fight against social injustice. Sierra’s works expose exploitation that is already there, even inside the institutions in which he shows his work. Sierra may pay someone minimum wage to sit in a gallery for four hours per day, but just down the corridor a security guard is paid the same amount to stand for often longer amounts of time.

In many ways, his work is the antithesis of Maria Eichhorn’s most recent work 5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours; in which she spent the budget for the show on closing the gallery and paying the staff to take the full duration of the show off work.

By highlighting these issues in the way that he does, Sierra stuns the viewer into action like the shock of cold water, and through this we are compelled to alter these types of situations in our own lives. His works afford the subjects a physicality that promotes much more intense feelings of empathy than can be created by plain numbers, seen upon a white page.

This works in much the same way as the documentation of war by photographers such as Don Mccullin. In a way, war photography is exploitative of those depicted dying and desolate, but the way in which these horrors are documented can promote viewers to help is incalculable. In this sense, the ends more than justify the means.

The exploitation of marginalised workers isn’t something that often makes headlines; it is the type of issue that is easy to sweep under the rug, and one that isn’t likely to sell many newspapers. Those who are being exploited are often fearful or unable to stand up for themselves, and if they do, they risk losing their only source of income.

As a society we are programmed to exploit, always seeking the most high-quality product or service for the lowest price. Phrases such as ‘bargain’ and ‘great value’ suggest a victory for the consumer at the expense of the producer. Commerce and the payment for services is not an altruistic system, it is predicated on cynicism and exploitation. Menial wage exploitation isn’t a bold or particularly visible form of injustice, and it will never garner headlines like racism, sexism, or homophobia. By creating his works, Sierra is fore-fronting these issues and making them unavoidable; we are unable to ignore such horror, and therein lies the beauty of his works. There is no stronger way of compelling help from those who are able to give it, than by exposing to them their silent complicity in the injustice that they are so repulsed by.

Through inaction and acquiescence, we are all complicit in certain forms of exploitation; from the cheaply made items we consume and dispose of; to the sweatshop-made fashion we buy. We are constantly looking for the best deal: the highest quality with the cheapest price. This frugality when misdirected can fuel the exploitation machine, it pushes prices for products and services lower, and as a direct consequence it is the disadvantaged that suffer the greatest losses.

Things (especially art) take their meaning from the viewer’s cache of similar past experience. The viewer attains their perspective by evaluating their feelings and understandings, seen through the prism of memory and how similar events have affected them.

If the positions of the artist’s ethical sensibilities, or the way those are portrayed are too obvious, the viewer reads the work as propaganda and becomes automatically and subconsciously defensive; or worse, dismissive. Art created didactically is better described as an applied art, or a piece of design, rather than true art — an idea summed up accurately by Gilda Williams: “If an artwork’s message is self-evident, maybe it’s just an illustration, a decorative non-entity, a well executed craft object, hardly counting as ‘significant’ art at all.”

This means that meaning and intent on the part of the artist must be vague, so as to be absorbed neutrally and thus ruminated upon by the viewer. The viewer can then decide through further consideration the ethical or philosophical undertones to the work, and can feel as if they have discovered them independently. This is the best way to convey ideas through art and produce real change. It leaves the decisions up to the viewer, and the gratification they receive when they feel like they have understood, or elucidated meaning from a work is profound.

Upon entering a gallery, the viewer is somewhat unguarded when it comes to political discourse, and is thus more easily affected. Certain media outlets, orators, and publications for example can be dismissed before they have had a chance to convey any information due to the viewer’s preconceptions about their bias, validity, or trustworthiness. This is less frequent in an art gallery however, which it is why the gallery setting is the perfect arena for information dissemination and discussion. The very act of placing an item or situation into a gallery setting opens it up to a level of scrutiny that the complexity of normal life suppresses.

What makes Sierra’s work all the more powerful is that it isn’t some grandiose attempt to topple governments or promote revolution; it simply shows how people can affect change in a very real and tangible way. The change Sierra is suggesting is the rejection of a system that isn’t working, and he is showing us exactly how to go about forcing that change. Upon seeing his work I cannot imagine any viewer not reevaluating how they see cheap labor, and changing their actions towards those less fortunate.

To borrow a phrase from Eugène Ionesco –

“To tear ourselves away from the everyday, from habit, from mental laziness which hides from us the strangeness of reality, we must receive something like a real bludgeon blow.”